Taking pictures of the sky!

Weather satellites are observational tools that give meteorologists a top-down view of the atmosphere. Satellites clue us into the strength of developing thunderstorms, hurricanes, and complement land-based observations such as radar and weather stations.

We have two types of satellites, polar-orbiting and geostationary. You may be more familiar with their acronyms, POES, and GOES.

In this post, I’ll break down visible satellite imagery. Get ready, there are going to be a lot of gorgeous pictures in this post.

What to wear this weekend? Ask POES!

POES, or Polar Operational Environmental Satellite, only orbits around the north and south poles. It is not at a fixed position, meaning it makes regular 360° around the globe 24 hours a day. POES provides continuous information. When you want to know the weather a few days out, we rely on the data gathered from POES.

The satellites also offer more detailed imagery because of the lower altitude. They provide data for a wide variety of weather sectors. So all the climate researchers, weather prediction models, volcanic eruption monitors, etc., have POES to thank for some critical observations.

Why isn’t it moving? The geostationary satellite

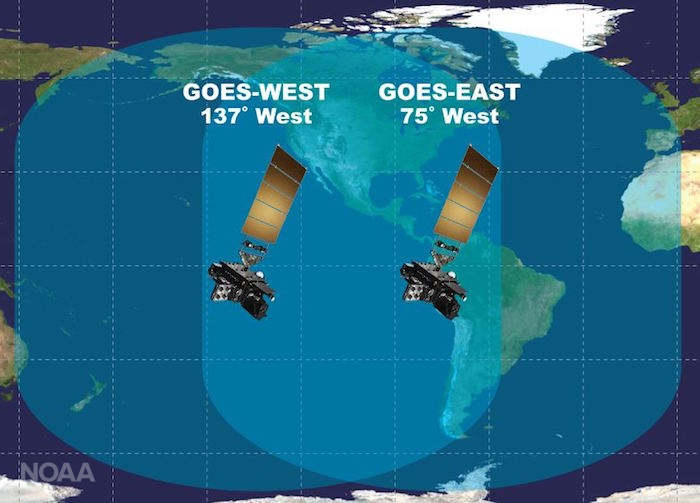

GOES, or Geostationary Environmental Orbiting Satellite, is at a fixed location above the Earth. Its orbital velocity is the same as Earth’s so to an observer, it appears stationary. Anytime you see me showing satellite imagery in my broadcasts, the image is from the GOES satellites. These satellites have a higher altitude producing a slightly lower resolution compared to POES satellites.

There are two GOES satellites, GOES-West and GOES-East, which operate simultaneously. We can get views of Alaska, Hawaii, the continental United States, and coverage of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Imagery is updated every 15 minutes, giving critical information on storms, tropical systems, snowstorms, and hurricanes.

Now let’s look at some pretty pictures

Satellites offer visible, infrared, and water vapor imagery. Visible satellite imagery takes a snapshot of the atmosphere from above, infrared focuses on the energy re-emitted from Earth, and water vapor imagery tells you about the moisture content in the atmosphere.

I’m just going to focus on visible imagery since that is my favorite. It’s only available during the day because there is no sunlight at night, which is a pitfall for which infrared and water vapor compensate.

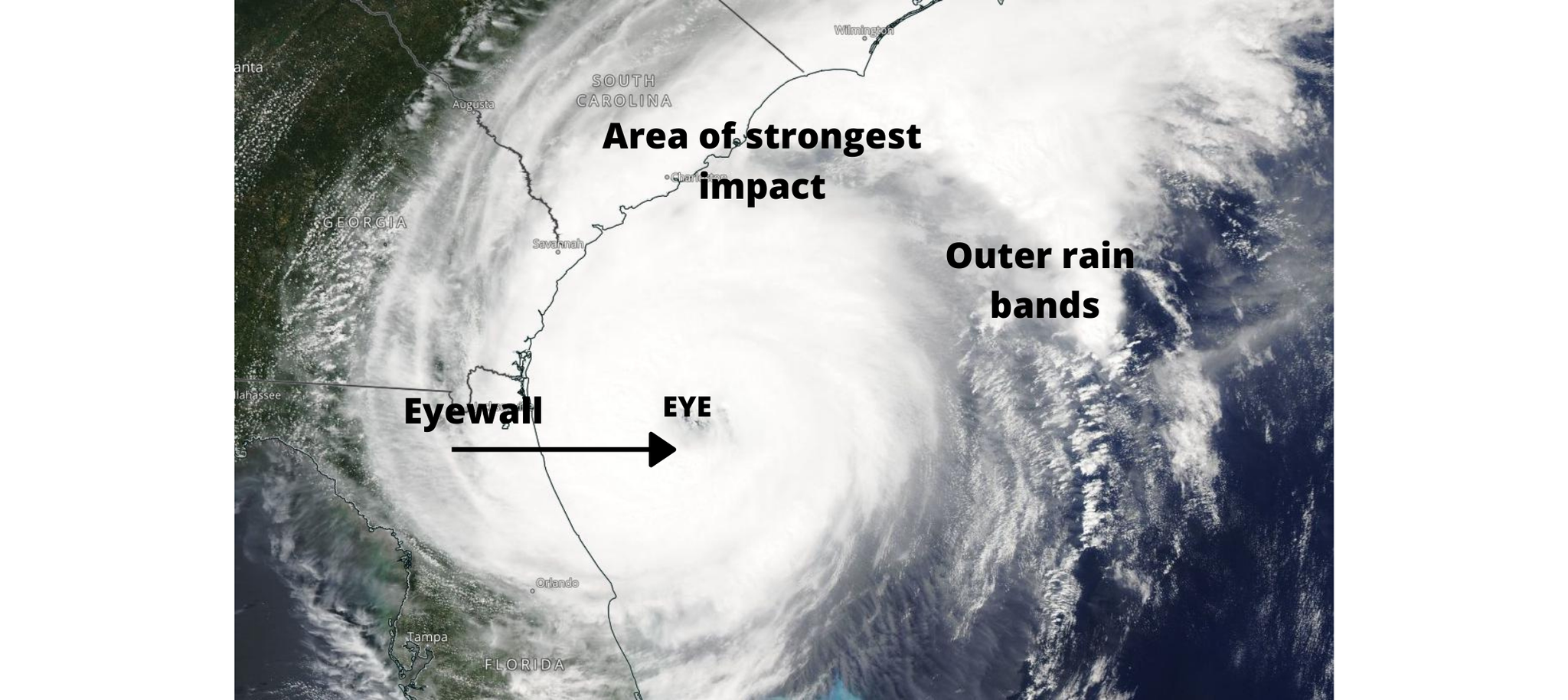

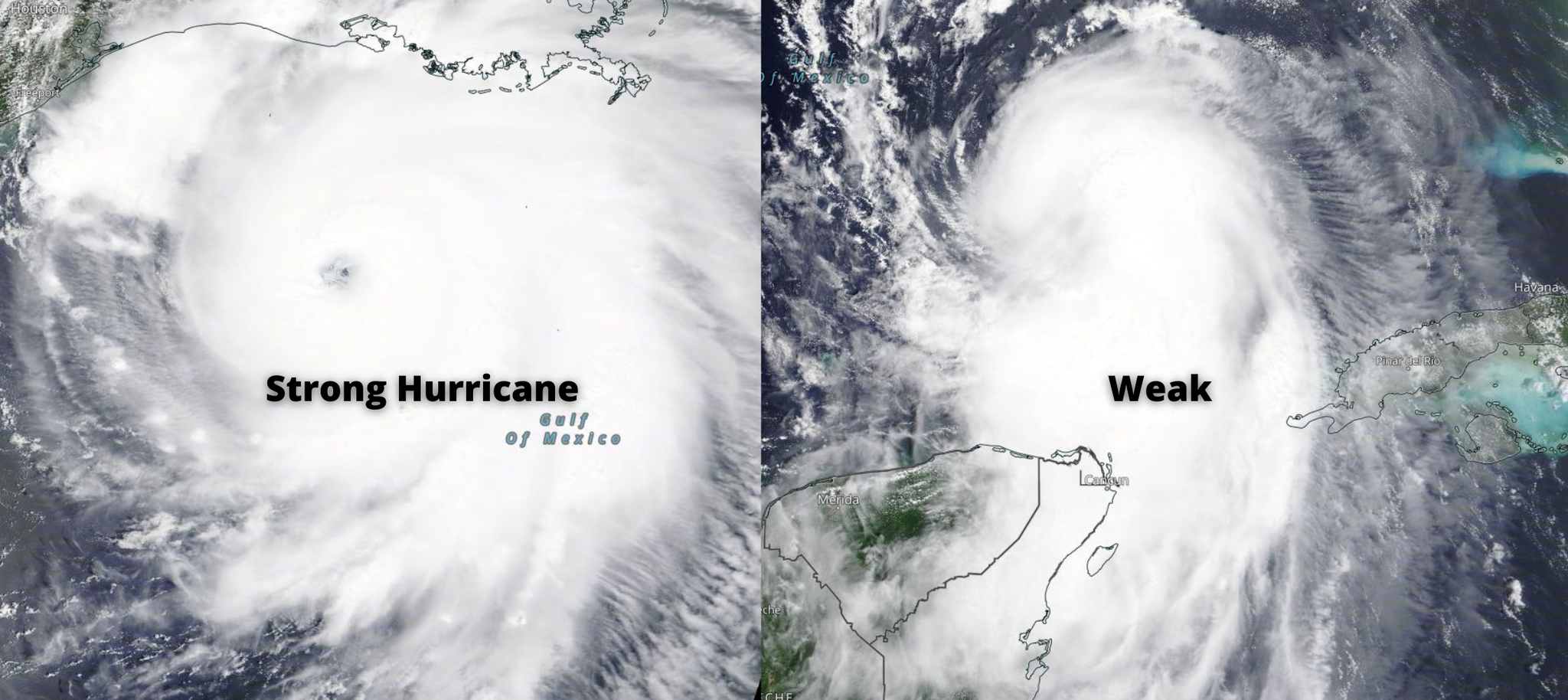

Hurricane

The strongest hurricanes will appear rounder on satellite imagery with well-defined eye structure. Stronger storms will also look more symmetric on satellites. If too much wind shear is present, the storm will lose the circular shape and symmetry. Hurricane-force winds are located around the eyewall, while tropical-storm-force winds stretch for hundreds of miles from the hurricane center.

Look at the example of Hurricane Laura, which struck Lake Charles, LA in 2020. Notice the lack of symmetry in the right image? As the hurricane rapidly strengthened, it developed a defined eye and eyewall with better symmetry and round shape.

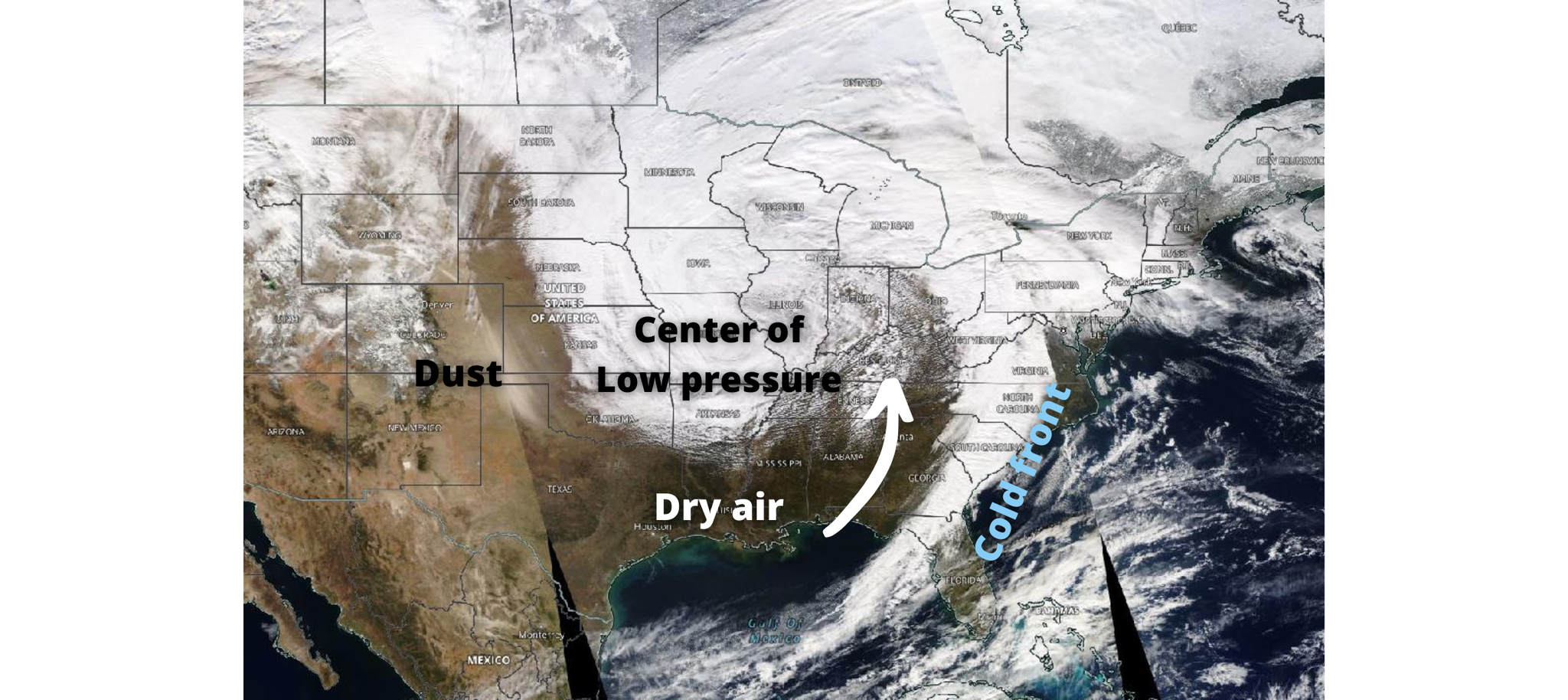

Snowstorm

The snapshot below is from a winter storm in mid-January. Notice the comma-shaped feature of the system? The center of low pressure is located in the Missouri/Illinois vicinity, while the cold front, as seen by trailing clouds, follows the east coast. This storm produced heavy snowfall stretching from Minnesota, to Iowa, along the Great Lakes, and into New England. Flurries were also reported in Alabama, Georgia, while 4 inches of snow fell in parts of Missouri.

Thunderstorm

Satellite imagery can tell us a lot about the strength of developing thunderstorms. The texture of satellite imagery and the height of the cloud tops give clues to the storm's development stage. Additionally, satellites can help pinpoint the location of weather fronts or even the dryline. Consider the satellite image of thunderstorms in the Texas Panhandle. These storms developed on March 13th of this year and were responsible for producing several tornados. Notice the large overshooting top of the northern storm? That is a good indicator of the maturity and strength of the supercell. Meanwhile, the southern storms are only just developing, and their cloud tops do not have a large spatial spread. These storms produced eight confirmed tornadoes, with two reaching EF-2 strength.

Other features

Satellite imagery can detect snow on the ground in the absence of clouds. While satellites are best viewed in motion to see snowfall (clouds will move, but the snow won't), notice the water features in mid-Missouri and the white coating around the lakes (darker grey colors). That is snow. You can also tell it apart from the clouds because of the difference in texture. The clouds in southern Missouri have a smoother texture.

While we can look up into the sky and identify clouds, we can also look down on the atmosphere and see them. From wispy cirrus to almost popcorn-like altocumulus clouds, satellite imagery is great for cloud identification.

Finally, satellite imagery is useful for wildfire detection. Smoke plumes are visible on satellite imagery, as the example below shows.

Satellite Pitfalls

The obvious pitfall of visible satellites is that the images are only available during the day. However, closer to sunrise or sunset, the images offer fewer details, limiting their ability if we have morning or evening storms. Another issue, they are looking down on the atmosphere and only see the topmost portion of clouds. They don't provide information on clouds sitting under other clouds. As with any meteorological tool, never use it alone, but rather in conjunction with other data available.

0 Comments Add a Comment?